America remains the world’s economic hegemon even as its share of the global economy has fallen and its politics have turned inwards. That is an unstable combination, says Patrick Foulis.

IN JUNE THIS year Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba, a giant Chinese e-commerce firm, addressed the Economic Club of New York, whose members include many Manhattan luminaries and Wall Street chiefs. Mr Ma’s message was that his company exists for the long-term good of society, a far cry from the creed of shareholder value followed by many in the room. He pledged to help America’s struggling small firms export to China’s 630m internet users, who between them now spend more online than Americans do. The venue for the event was the Waldorf Astoria hotel, which, when it opened in 1931, in the midst of the Depression, was hailed by President Herbert Hoover as “an exhibition of confidence and courage to the whole nation”. Today the Waldorf is owned by a Chinese insurance firm run by Deng Xiaoping’s grandson-in-law. The whole event seemed to symbolise a change in the world’s economic order.

Yet as a parable of American decline that would be too neat. The lesson from Mr Ma’s big day in the Big Apple is more subtle: that America remains the world’s indispensable economy, dominating some of the brainiest and most complex parts of human endeavour. Alibaba is listed in New York, not on Shanghai’s bourse, whose gyrations this year have alienated investors. Four of the six banks that underwrote Alibaba’s flotation were American. Alibaba makes only 9% of its sales outside China (and has just hired a former Goldman Sachs executive to increase that share). The Waldorf is run by an American firm, Hilton, that does well out of owning intellectual-property rights worldwide. Days after his speech Mr Ma spent $23m on a mansion in New York state’s Adirondack mountains. No doubt he will enjoy the trout streams, but like many Chinese tycoons he may also want a bolthole in a country that embraces the rule of law. Two months later China devalued its currency, causing panic about its economy.

This special report will examine the paradox illustrated by Mr Ma’s speech. It will argue that America is a sticky economic superpower whose capacity to influence the world economy will linger and even strengthen in some respects, even though its economic weight in the world is declining. For some, this is a welcome prospect. Hillary Clinton, a front-runner for the job of America’s next president, wrote last year: “For anyone, anywhere, who wonders whether the United States still has what it takes to lead…for me the answer is a resounding ‘yes’…everything that I have done and seen has convinced me that America remains the indispensable nation.” But if handled badly, the growing gap between America’s economic weight and its power will cause frustration and instability.

Power is the capacity to compel another to do what they otherwise would not. It can be exercised through coercion, by setting rules or by engendering expectations and loyalties. American power is sometimes defined so broadly that it includes both the flight decks of the USS Abraham Lincoln and the legs of Taylor Swift. This report will focus on a narrower point: how America’s grip on the global economy helps, enriches, organises, bosses and annoys the rest of the world . This kind of power is often wielded inadvertently: for example, America has no desire to run India, yet India’s economy is affected by the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy; and two of the subcontinent’s leading industries, technology and pharmaceuticals, are subject to American rules that are a de facto world standard.

American economic dominance has never been absolute. Between 1946 and 1991 the Soviet Union’s empire of queues and rust aspired to be a rival model. From the 1970s onwards Europe pursued closer integration partly as a counterweight to America; the idea of a single European currency gained momentum as Europeans grumbled about the ascendancy of the dollar. Japan appeared to pose a threat in the 1980s and in its pomp tried to persuade Asia to join a yen zone. Even when the so-called Washington Consensus of American-inspired liberal economic policies was at its peak in the 1990s, many countries, most notably China, ignored it. But until recently one thing was clear: America had the biggest weight of any country in global GDP and trade.

In the first change in the world economic order since 1920-45, when America overtook Britain, that dominance is now being eroded. As a share of world GDP, America and China (including Hong Kong) are neck and neck at 16% and 17% respectively, measured at purchasing-power parity. At market exchange rates a fair gap remains, with America at 23% and China at 14%. By a composite measure of raw clout—share of world GDP, trade and cumulative net foreign investment—China has probably overtaken America already, according to Arvind Subramanian, an economist (see chart). Even if China’s economy grows more slowly from now on, at 5-6% a year, its strength on such measures will increase.

The experience of the 20th century suggests that such a transition can happen fast. In 1907 America lacked a central bank and suffered a banking collapse, but by the 1920s the dollar rivalled the pound sterling as the world’s most widely used and trusted currency. If the past is a guide, China could surpass America in the blink of an eye, giving it the heft to issue the world’s reserve currency and set the rules of trade and finance. A plurality of people polled by the Pew Research Centre around the world believe that China will become the world’s leading economic power. Those aged under 30 are most likely to believe they will live in a Chinese epoch.

But any reordering of the world economy’s architecture will not be as fast or decisive as it was last time. For one thing, the contest is more balanced. America is far stronger than Britain was at its moment of precipitous decline, and China is weaker today than America was when it took off. For all its efforts to promote its currency and its institutions, the Middle Kingdom is a middle-income country with immature financial markets and without the rule of law. The absence of democracy, too, may be a serious drawback.

Today’s world also relies on a vastly bigger edifice of trade and financial contracts that require continuity. Trade levels and the stock of foreign assets and liabilities are five to ten times higher than they were in the 1970s and far larger than at their previous peak just before the first world war. The speed and complexity of capital flows surpass anything the world has ever seen before. Britain and America were allies, which made the transfer of power orderly, if often humiliating for the declining power. Having squashed Britain’s global pretensions at the Bretton Woods conference on the international monetary and financial order in 1944, America helped cushion its financial collapse in 1945-49. China and America are not allies. The greater complexity and risk involved in remaking the global order today create a powerful incentive for current incumbents to keep things as they are.

Last, the nature of economic activity has changed, shifting towards intangible, globalised services (such as cloud computing and computerised financial trading) in a way that may allow America to exert dominance by remote control.

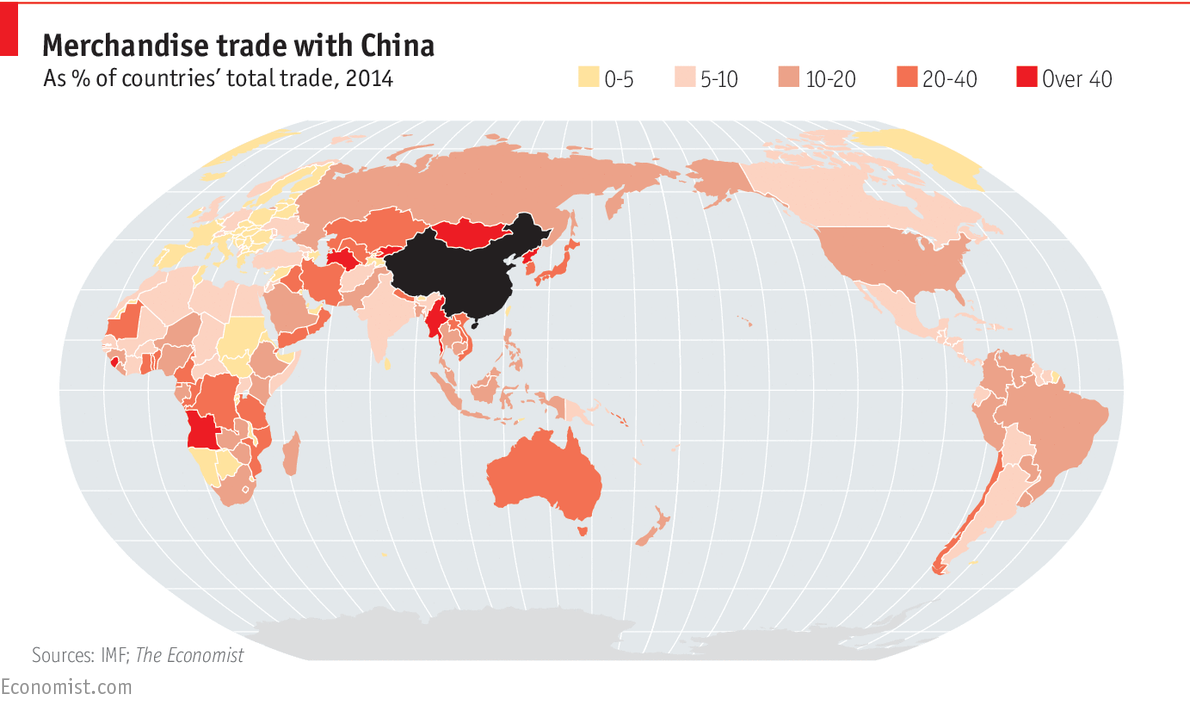

Economists, Tea-Partiers, trade unionists and Bruce Springsteen have chronicled America’s slide on traditional measures of economic and institutional prowess. Judged by its share of world steel production, manufacturing, merchandise trade, transport and commodities production and consumption, the country is going to the dogs (see chart). The number of countries for which America is the biggest export market has dropped from 44 in 1994 to 32 now. Over the same period the equivalent figure for China has risen from two to 43.

America’s lead in other areas, such as research-and-development spending, technology equipment and consumer brands, is no longer as comfortable as it was. Many of the world’s most valuable firms are still American, but this overstates their clout abroad: their share of the stock of international corporate investment has fallen from 39% in 1999 to 24%.

America still shines in a number of fields. It has 15 of the world’s 20 leading universities. Its Food and Drug Administration is the global benchmark for the efficacy of a new medicine. A patent registered in New York is far more credible than one booked in Shanghai. And Hollywood’s domination of the world’s box offices is as eternal as a Californian film star’s youth.

What is less widely acknowledged is that in some domains America’s clout is increasing. The country has demonstrated an astonishing capacity to dominate each new generation of technology. It is now presiding over a new era based on the cloud, e-commerce, social media and the sharing economy. These products go global faster and penetrate more deeply into people’s minds and jobs than anything Silicon Valley has invented before, affecting everyone from cabbies to philanderers to despots.

Facebook and Google do a majority of their business abroad, and that share is rising. When Microsoft was at the height of its powers in 2000, it made less than a third of its sales overseas. American firms now host 61% of the world’s social-media users, undertake 91% of its searches and invented the operating systems of 99% of its smartphone users. China’s internet firms, including Mr Ma’s, are both protected and trapped behind China’s “Great Firewall”.

America’s dominance of the commanding heights of global finance and the world monetary system has risen. The global market share of Wall Street investment banks has increased to 50% as European firms have shrunk and Asian aspirants have trodden water. American fund managers run 55% of the world’s assets under management, up from 44% a decade ago, reflecting the growth of shadow banking and new investment vehicles such as exchange-traded funds. Global capital flows, larger than at any time in history, move in rhythm with the VIX, a measure of volatility on America’s stockmarkets.

Power through neglect

One of the oddities of globalisation is that although America’s trade footprint has shrunk, its monetary footprint has not. The Federal Reserve is the reluctant master of this system, its position cemented by the policies put in place to fight the 2007-08 financial crisis. When the Fed changes course, trillions of dollars follow it around the world. America’s indifference towards the IMF and World Bank, institutions it created to govern the system and over which it has vetoes, reflects power through neglect.

The position of the dollar, widely seen as a pillar of soft power, has strengthened. Foreign demand for dollars allows America’s government to borrow more cheaply that it otherwise could, and the country earns seigniorage from issuing bank notes around the world. America’s firms can trade abroad with less currency risk, and its people can spend more than they save with greater impunity than anyone else. Even when a global crisis starts in America it is the safe haven to which investors rush, and foreigners accumulate dollars as a safety buffer.

Since the attacks of September 11th 2001, America has emphatically asserted control over the dollar payment system at the heart of global trade and finance. Hostile states, companies or people can be cut off from it, as Iran, Burmese tycoons, Russian politicians and FIFA’s football buffoons have found to their cost. The threat of this sanction has given America an enhanced extraterritorial reach.

Finance and technology are already a battleground for sovereignty, as Europe’s pursuit of Google through antitrust cases has shown. So for America to lay a claim to running the world economy’s central nervous system even though it is no longer its dominant economic power would be the ultimate expression of its exceptionalism. The country would need to show an extraordinarily deft touch. It would have to act, and to be seen as acting, in the collective interest.

America’s political system has shown itself capable of great leadership in the past, not least during and after the second world war. Today it is falling short of these ideals. The global financial crisis proved that America always does the right thing in the end, but only after exhausting all the alternatives. The Federal Reserve provided liquidity to the world, and with a gun to its head Congress stumped up the cash to rescue American financial firms. But since then America’s political system has flirted with sovereign default, refused to reform or fund the IMF, obstructed China’s efforts to set up its own international institutions, imposed dramatic fines on foreign banks and excluded a growing list of foreigners from the dollar system.

The idea that America’s political system does not feel obliged to meet what self-interested foreigners present as its global economic responsibilities is nothing new. When informed about a speculative attack against Italy’s currency in 1972, Richard Nixon snapped: “I don’t give a shit about the lira.” But the country’s current indifference may be more than a temporary lull. America’s middle class is unhappy with globalisation and its politics are deeply polarised.

If America failed to live up to expectations, what would that mean for the rest of the world? For the moment it is easy for America’s policymakers and politicians to be complacent: China’s aura of competence has been damaged by its recent economic troubles, and America has the world’s perkiest economy, admittedly in a sluggish field. But it is important to be clear-headed about the long-term choices. America cannot expect effortlessly to dominate global finance and technology even as its share of world trade and GDP declines and it becomes ever more inward-looking.

This special report will argue that the present trajectory is bound to cause a host of problems. The world’s monetary system will become more prone to crises, and America will not be able to isolate itself from their potential costs. Other countries, led by China, will create their own defences, balkanising the rules of technology, trade and finance. The challenge is to create an architecture that can cope with America’s status as a sticky superpower. The next article will explain why its internal politics have made this ever more difficult.

Expositores: Oscar Vidarte (PUCP) Fernando González Vigil (Universidad del Pacífico) Inscripciones aquí. Leer más

Una retrospectiva para entender los próximos cuatro años. Leer más

En la conferencia se hará una presentación de los temas más relevantes del proceso de negociación se llevó a cabo desde el 2012, así como del acuerdo de paz firmado entre el Gobierno colombiano y la guerrilla de las FARC a finales del 2016. Se analizarán los desafíos y las... Leer más

El Observatorio de las Relaciones Peruano-Norteamericanas (ORPN) de la Universidad del Pacífico es un programa encargado de analizar y difundir información relevante sobre la situación política, económica y social de Estados Unidos y analizar, desde una perspectiva multidisciplinaria, su efecto en las relaciones bilaterales con el Perú.

© 2026 Universidad del Pacífico - Departamento Académico de Humanidades. Todos los derechos reservados.