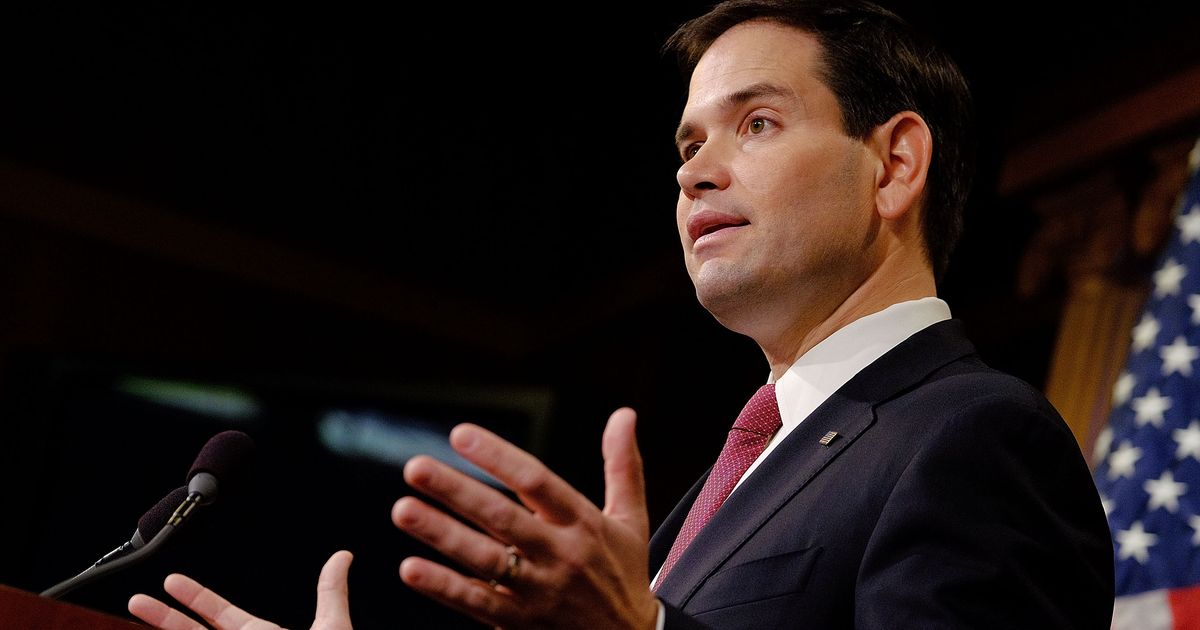

Three days before Florida’s climactic primary, Marco Rubio sank deep into a black leather armchair on his campaign bus. He had just spent 25 minutes smiling wide for supporters at a high-end boutique selling $150 candles. “Don’t forget to vote on Tuesday!” he shouted from the third step of a wood-paneled staircase. Now, on his parked bus, the afternoon sunlight shut out by drawn blinds, the smile was gone. The candidate knew it was already over.

“There will be a reckoning,” he warned.

Story Continued Below

“There will be a reckoning in the mainstream media, where all these networks and cable networks are going to have to ask themselves why did they give so much coverage for the sake of ratings,” he said. “There will be a reckoning in the conservative movement, where a lot of people who for a long time have espoused conservative principles seem to not care about those anymore in rallying around Donald Trump because they like his attitude.

“I think there are a lot of people in the conservative movement who are going to spend years and years explaining to people how they fell into this and how they allowed this to happen.”

For now, though, it is Rubio’s reckoning that’s at hand. And not just because of Trump or cable television networks.

Rubio’s strategy was always an inside straight—overly reliant on a candidate’s ability to dominate free national media in order to outperform, outwit and eventually outlast a wide field of rivals. It was sketched out by an inner circle of advisers who believed they could eschew the very fundamentals of presidential campaigning because they had a candidate who transcended.

That’s exactly what happened in 2016; it just turned out Rubio wasn’t the one transcending.

Even before his picturesque launch at symbolic Freedom Tower in Miami last spring, Rubio’s aides were hardly the only ones who saw in Rubio an answer to the Republican Party’s prayers: a young, charismatic and Hispanic conservative, the son of a bartender and a maid with remarkably broad appeal across a GOP spectrum riven by ideological and stylistic divisions. He’d been plastered on the cover of Time as “The Republican Savior.” Rubio was the kind of rare talent who could win a primary and then articulate a conservative message that resonated in a fast-changing country in the general.

And he scared the daylights out of the Democrats.

So while other campaigns touted “shock and awe” fundraising networks and precise, psychographic analytics and voter targeting operations, Rubio’s tight-knit group of mostly 40-something bros believed wholeheartedly that they didn’t need a specific early-state win. They didn’t need a particular political base. They didn’t need to talk process. They didn’t need a ground game. They didn’t need to be the immediate front-runner.

All they needed was Marco.

Their confidence bordered on arrogance. Sure, his closest advisers—campaign manager Terry Sullivan and media strategists Todd Harris and Heath Thompson—were right that their candidate was likable. He began the race as the second choice of many Republican primary voters. They just never figured out how to make voters embrace him as their first.

Trump was drawing away the cameras they had banked on lifting their rising star, sucking up all the media attention as he dominated media cycle after media cycle, setting the parameters of the 2016 debate, day after day. Suddenly, their telegenic candidate couldn’t get on TV.

And when Rubio stumbled, as all candidates do, there was no infrastructure to catch him, no field program to lift his support, no base to fall back upon.

All they had was Marco.

***

As Jeb Bush was quickly beset by leaks, backbiting and inflated expectations, Rubio’s campaign more closely resembled the Barack Obama model of 2008 from the start. It was a close-knit group, led by Sullivan, Thompson and Harris, with Alex Conant, Rubio’s communications director since 2011, Rich Beeson, the deputy campaign manager, pollster Whit Ayers and a few others in the innermost circle.

They held conference calls three times a week to stay on the same page, and based their headquarters only a few blocks from Capitol Hill to better coordinate with Rubio when the Senate was in session. Sullivan ran a tight ship. In the early months of the campaign, he insisted on personally signing off on every expense above $500. The limit was later relaxed but symbolic of a campaign that knew it had to scrimp to compete with Bush, whose super PAC hauled in $100 million in the first half of 2015.

The campaign spared no expense in setting up events to be television-friendly. There were invariably press risers, tidy backdrops and television lighting to portray Rubio, quite literally, in the best imaginable light.

But one of the things Sullivan seemed least interested in was field offices. The campaign would force volunteers and supporters to pay for their own yard signs, posters and bumper stickers.

Rubio seemed to agree. In August, he was due to open his Iowa state headquarters the morning after flipping pork chops at the state fair, but he bailed at the last minute. The reason: heading back to Florida for his children’s start of school. The grand opening would be delayed for 10 days, and it would occur without Rubio. He wouldn’t announce a state director to run operations in the crucial caucuses for another month.

It was a fitting episode for a campaign that had bragged about how staff could work just as well out of a Starbucks with a laptop. The campaign wouldn’t announce supporters in Iowa’s various regions until January 2016, and only then under intensifying pressure from allies. And when campaign officials announced their “field offices,” they wouldn’t say exactly where they actually were, making it all but impossible for volunteers to volunteer.

It’s not that Rubio’s team didn’t know the data science that powered Obama’s two campaigns or that studies showed that door knocks and personal phone calls are among the most effective means to get out the vote. It’s that they’re expensive and time-consuming. And Rubio’s team thought they had figured out a better way: targeting exactly their voters with pinpoint precision online, on TV and in the mail.

“It’s almost like they wanted to prove they could win without doing some of the stuff people have to do to win,” said one Rubio supporter very familiar with the campaign’s planning. “Were they just fucking lazy or arrogant?”

In fact, they had designed a campaign to fit neatly with Rubio’s own conception of himself as master political communicator.

“Marco is convinced, and perhaps rightly so, that he has the skills to convince anyone,” said Dan Gelber, who served for eight years in the Florida Legislature with Rubio, including two as the Democratic counterpart when Rubio was GOP speaker. “He really believes that if you give him an audience, he can turn them to his way of thinking.”

***

Donors were unnerved by it, though. So Terry Sullivan outlined the plans to some of Rubio’s supporters at a closed-door strategy session at the Bellagio hotel in Las Vegas in October.

The campaign’s goal, Sullivan explained, was simply to put Rubio “in front of as many voters as possible as often as possible,” according to an attendee. And that meant getting free media coverage and buying paid television ads. So the campaign had locked in ad rates early—paying as little as 10 cents for every dollar spent by Bush’s super PAC. At times, they’d spend far less than Bush’s allies and still out-advertise them.

The team wanted Marco to sell himself on TV, not rely on second-rate surrogates or volunteers. And that meant less focus on door-knocking or volunteer phone-calling.

Donors and early-state supporters who had grown accustomed to presidential-level coddling and attention pushed back. And by December, Optimus, the firm paid nearly $900,000 to run Rubio’s analytics operation, prepared a public memo to quiet the critics. The memo described a hypothetical Midwestern state with 150,000 likely voters (roughly the expected Iowa turnout at the time) and one candidate at 20 percent, trailing another at 30 percent.

It was clear to everyone it was about Rubio and Iowa.

In it, Optimus made the case that running a ground game “missed the elephant in the room” as it nudged support up less than 1 percentage point. “You’ve got a 10 point gap you need to close,” the memo read.

“All this is not to say that door knocking doesn’t work. We know it does,” the memo concluded.

Sullivan put it most succinctly to the New York Times in December: “More people in Iowa see Marco on ‘Fox and Friends’ than see Marco when he is in Iowa.”

The ground-free strategy surprised Democrats and even some of Rubio’s rivals.

“This isn’t even a question in the mind of anyone who’s worked on presidential campaigns,” Dan Pfieffer, a former senior adviser to President Obama, told POLITICO earlier this year. “You have to build an extensive and aggressive ground operation to win.”

“The weirdest thing is that we’re debating this,” Pfieffer added.

Ted Cruz had invested more in ground operations than any other Republican, and his campaign manager, Jeff Roe, told POLITICO he was surprised how few ground troops any of his opponents were mobilizing.

«It’s a huge investment; it’s a huge investment of resources when a lot of people might not know how many resources they have, so I understand why they don’t do it,” Roe said. But there’s an advantage: «The ground game just never goes away.»

Expositores: Oscar Vidarte (PUCP) Fernando González Vigil (Universidad del Pacífico) Inscripciones aquí. Leer más

Una retrospectiva para entender los próximos cuatro años. Leer más

En la conferencia se hará una presentación de los temas más relevantes del proceso de negociación se llevó a cabo desde el 2012, así como del acuerdo de paz firmado entre el Gobierno colombiano y la guerrilla de las FARC a finales del 2016. Se analizarán los desafíos y las... Leer más

El Observatorio de las Relaciones Peruano-Norteamericanas (ORPN) de la Universidad del Pacífico es un programa encargado de analizar y difundir información relevante sobre la situación política, económica y social de Estados Unidos y analizar, desde una perspectiva multidisciplinaria, su efecto en las relaciones bilaterales con el Perú.

© 2026 Universidad del Pacífico - Departamento Académico de Humanidades. Todos los derechos reservados.