Criminal law looks backward toward offenses committed. The object of impeachment is not to exact vengeance. It is to protect the public against future acts of recklessness or abuse. Consequently, the issue in deciding whether Mr. Trump is liable to impeachment is less what happened in the Oval Office between him and Mr. Comey than what those events say about what will happen in similar situations in the future. That is not a case for casual impeachment. On the contrary, since it is harder to predict future acts than to prove what has already occurred, such a standard may be harder to meet.

Our tendency to read the impeachment power in an overly legalistic way, which is ratified by 230 years of excessive timidity about its use, obscures the political rather than juridical nature of the device. The Constitution applies presidential impeachment to “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” The famous latter phrase does not refer to offenses like burglary on the one hand or loitering on the other. If it did, impeachment would be available for casual transgressions, which no framer of the Constitution intended.

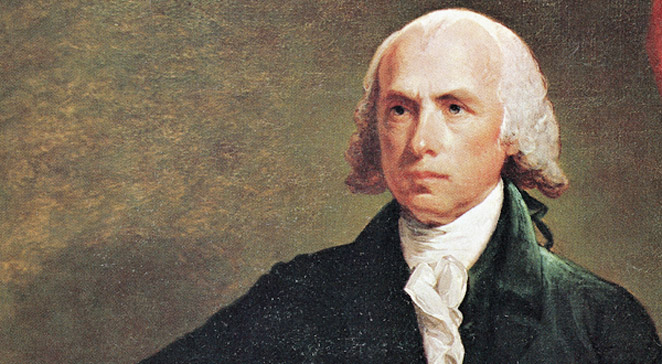

The phrase dates in American constitutionalism to the founder George Mason’s proposal to make the president liable to impeachment not just for treason and bribery — the original formulation at the Constitutional Convention — but also for what he called “maladministration.” His fellow framer James Madison objected to the vagueness of the term, so Mason substituted “high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” That phrase, in turn, is traceable to the British legal commentator William Blackstone, a contemporary who was revered in colonial America, who applied it to the “mal-administration of high officers,” among other things.

Mason’s intent was clearly to delineate a political category, something Alexander Hamilton — who did not shrink in the defense of executive power — recognized in Federalist 65, which says that impeachment applied to offenses “of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL, as they related chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself

The victim Hamilton identified — “the society itself” — defined the nature of the offense. Earlier, at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Madison had indicated the same understanding. Note, crucially, the purpose for which he said impeachment should be available: “Mr. Madison thought it indispensable that some provision should be made for defending the community against the incapacity, negligence or perfidy of the Chief Magistrate.”

The tendency to read “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” too literally is one reason the 25th amendment, which treats presidential incapacity as though it requires a special constitutional mechanism when in fact one was already in place, became necessary. It is also why, in a development that surely would have surprised Hamilton and Madison alike, the republic has managed 23 decades without a successful impeachment and conviction, the resignation of President Richard Nixon notwithstanding.

The political nature of the impeachment authority does not mean it is merely a contest over power. Still less is it supposed to rehash electoral disputes. Instead, the point is that because its purpose is to “defend the community” rather than to punish an individual, the standards of a criminal trial do not apply. The Constitution’s specification that prosecuting an individual for an act for which he or she was impeached does not constitute double jeopardy reinforces this understanding.

The prophylactic rather than punitive character of the impeachment power still, of course, requires an offense. But the offense indicates a pattern on the basis of which future behavior can be predicted. The idea is not to humiliate the president or to cause him to suffer by the loss of his office. It is to protect the public against his negligence or abuse.

In this sense, it does not matter whether Mr. Trump explicitly intended to obstruct justice when he reportedly attempted to cajole Mr. Comey. The determination Congress must make is what its level of confidence is that Mr. Trump can be trusted not to abuse the levers of power in similar ways if he continues to hold them. On another front, there is little question that he committed no crime when he leaked classified information to the Russian ambassador. But that, too, is not the question impeachment poses. The issue is whether Madison’s community and Hamilton’s society need to be defended against similar behavior in the future.

There are reasonable arguments to be made that despite all the controversies, the president can demonstrate the discipline his office requires. Others may assert that the acts of which he is accused did not occur, did not occur the way they were reported, or did not constitute high crimes or misdemeanors if they did occur.

The evidence should be carefully gathered, a process in which Robert S. Mueller III, acting as special counsel, will help considerably. But Mr. Mueller is no substitute for Congress’s independent responsibilities of investigation and sober evaluation. The question is by what standards they should conduct this work, and that question provides an opportunity to correct the mistaken assumption according to which presidents can forfeit the public trust only by committing what the law recognizes as a crime. That is a poor bar for a mature republic to set. It is not the one a newborn republic established.

And that is why the idea that the conversation about impeachment is simply a political persecution of a man who is technically innocent of a literal crime not only jumps the investigatory gun. It misses the constitutional point.