omorrow, Brookings will host a forum titled, “The role of minority voters in the 2016 election.” Over the past several election cycles, minority voters have played an increasingly important role in determining who is elected president. That trend is likely to continue as turnout rates among minority demographic groups increases and political strategists note the importance of tailoring messages to such groups to gain an electoral advantage.

Wednesday’s event will feature experts to discuss how the rise of political power among minority groups has followed the increased salience of issues like immigration, criminal justice reform, and racial bias an inequality. How the 2016 presidential candidates engage with communities of color has become a significant part of the analysis and media coverage of this election. This event will offer a deep dive into those issues.

In advance of the event, it is important to discuss some of the key data that will likely come up during the discussion and question and answer period. These data show five ways minority populations have changed the demographic landscape of US elections and how that transformation will continue in 2016 and beyond.

Minority Millennials should not be taken for granted

Recent polling from The Black Youth Project at the University of Chicago looked at millennials’ views of the issues of the day and the 2016 presidential candidates. While millennials tend to favor Democrats, particularly in presidential elections, and communities of color vote similarly, the differences among young people of color show that millennials can’t necessarily be counted as a single voting bloc. Additionally, while minority millennials do favor the Democratic presidential candidate by significant margins—a pattern that is true for African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans aged 18-30, a significant number of those polled are considering not voting. This suggests that turnout will be critical if Clinton seeks to capitalize on her support among these voters.

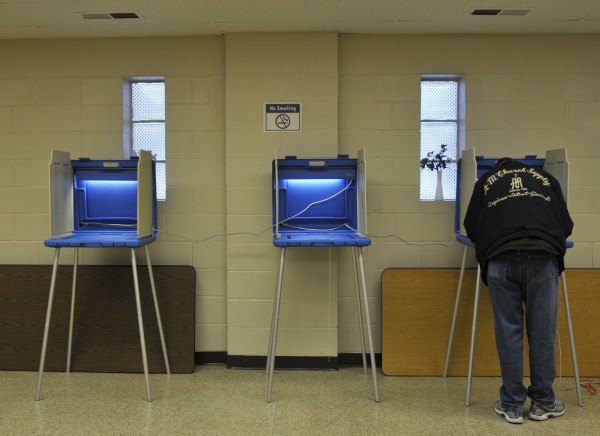

Turnout and GOTV efforts are critical

The ability of groups of people to influence election depends in part on the size of that group and in large part on how many voters from that group turn out to vote. If voices are heard—ballots are cast—political clout can be significant. A look at turnout rates among minority populations show why political power among communities of color has increased. Since the year 2000, turnout rates among African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans have increased significantly. Table 2 shows how these data track. For example, Latino and Asian American turnout has exploded from less than 30 percent in 2000 to nearly 50 percent in 2012. African American Turnout has increased as well, outpacing white turnout in the 2012 race—for the first time in history.

Communities of color can empower Democrats

It is no secret that minority voters tend to vote for Democratic presidential candidates over Republican candidates. However, a look at voting data shows how large those disparities are and how those voting patterns have changed over the past several election cycles. According to Roper Center data on how different groups voted, the Democratic share of the vote has risen among all minority groups since the 2000 presidential election, easily exceeding 50 percent across all groups. By comparison, Clinton is beating Trump 70 percent to 2 percent among African American millennials, 59 percent to 16 percent among Asian American millennials, and 60 percent to ten percent among Latino millennials.

Minority power in key swing states

Not every swing state has a significant non-white population. New Hampshire and Iowa, for example, are among the whitest states in the U.S. However, in several other 2016 swing states, African America, Latino, and Asian American voters compose significant segments of state populations and that presence—combined with preferences for Democratic candidates—can have huge effects on who becomes the 45th President of the United States. Tables 4, 5, and 6 show the percentage of swing state populations among African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans respectively. Those charts also show the changes in the sizes of minority populations since 2008. Those changes help explain why minority political clout has grown, why it matters in key states, and what the consequences of those changes may be in 2016.

White political power is decreasing steadily

Connected to rises in political clout among communities of color is the decrease in the size of white populations in the U.S. generally and in key swing states. For example, in Arizona, Georgia, and Nevada, since 2008, the white share of the population has dropped to a slim majority of the population. In every swing state, the share of the white population has dropped since 2008 and in four states—Florida, Georgia, Nevada, and Virginia—that drop has been larger than the national average. In coverage of the 2016 presidential race, much has been discussed about Republicans’ ability to win the White House by relying solely on white voters—in the face of increasing losses in voting support among minorities. These data suggest how precarious of a gamble that is and one that is likely to be a sure path to defeat in future elections—if it is not already a losing bet.

Expositores: Oscar Vidarte (PUCP) Fernando González Vigil (Universidad del Pacífico) Inscripciones aquí. Leer más

Una retrospectiva para entender los próximos cuatro años. Leer más

En la conferencia se hará una presentación de los temas más relevantes del proceso de negociación se llevó a cabo desde el 2012, así como del acuerdo de paz firmado entre el Gobierno colombiano y la guerrilla de las FARC a finales del 2016. Se analizarán los desafíos y las... Leer más

El Observatorio de las Relaciones Peruano-Norteamericanas (ORPN) de la Universidad del Pacífico es un programa encargado de analizar y difundir información relevante sobre la situación política, económica y social de Estados Unidos y analizar, desde una perspectiva multidisciplinaria, su efecto en las relaciones bilaterales con el Perú.

© 2026 Universidad del Pacífico - Departamento Académico de Humanidades. Todos los derechos reservados.