Echoes of Watergate are everywhere these days.

President Trump’s firing of the F.B.I. director, James Comey, drew immediate comparisons to Richard Nixon’s order to dismiss the special Watergate prosecutor, Archibald Cox, in October 1973. Mr. Trump’s insinuation that he had taped meetings with Mr. Comey recalled the secret White House recordings that ultimately brought a president down. And the demands today for aggressive congressional investigations into possible collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia during the 2016 election remind me of the pressures on House and Senate investigations into the 1972 Nixon presidential campaign.

As a 27-year-old investigator for the Senate’s Watergate committee, I saw up close how that inquiry unfolded. Our committee helped unearth the most damning evidence against the president. But the special prosecutor’s office played a crucial role in making that evidence public. The two entities overcame partisan and jurisdictional conflicts to bring about the president’s resignation — and their work offers a valuable lesson for today, when hyper-partisanship dominates.

The Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities was created in February 1973 after John Sirica, the Republican federal judge presiding over the trial of men charged with breaking into Democratic Party offices at the Watergate, raised doubts about whether they had acted alone, skepticism spurred by articles in The Washington Post. Judge Sirica’s harsh sentences broke the burglars’ silence.

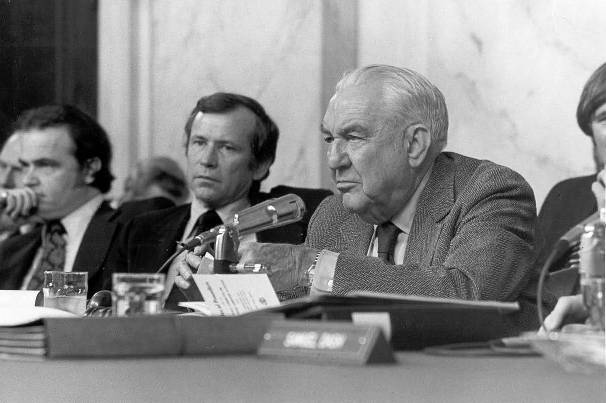

Led by its Democratic chairman, Sam J. Ervin Jr. of North Carolina, and its Republican vice chairman, Howard H. Baker Jr. of Tennessee, the committee tried to present a bipartisan image. Behind closed doors it was anything but. Our star witness, John Dean, the former White House counsel, warned the Democratic staff privately that while he oversaw the White House cover-up for Mr. Nixon, Mr. Baker and the minority counsel, Fred Thompson, were trying to thwart the congressional investigation.

Before the hearings began, the Democratic staff decided not to share details about Mr. Dean’s damaging evidence with Republican colleagues. At a contentious executive session, Mr. Baker opposed plans by the committee’s chief counsel, Samuel Dash, to use the hearings to explain political and criminal events preceding the break-in. On Mr. Dash’s orders, I followed Mr. Baker’s top aide and discovered he was meeting secretly with the White House counsel, J. Fred Buzhardt. We confronted Mr. Baker, and the aide resigned.

When the televised hearings opened in May 1973, Mr. Baker and Mr. Thompson continued to work behind the scenes to prevent the inquiry from focusing on Mr. Nixon. In July, a committee stenographer slipped me a copy of notes from secret conversations in which Mr. Buzhardt provided Mr. Thompson lengthy quotations from Mr. Nixon’s one-on-one meetings with Mr. Dean. Mr. Baker and Mr. Thompson tried to use that information to suggest during cross-examination that Mr. Dean was the sole author of the cover-up.

On July 13, we questioned a Nixon aide, Alexander Butterfield, about Mr. Thompson’s notes. Pressed to explain how he had obtained such precise quotations from the Nixon-Dean meetings, Mr. Butterfield revealed that the president had a taping system in his offices.

Once Mr. Baker’s collusion with the White House was revealed in Mr. Thompson’s memo, I could see his opposition to obtaining the tapes melt, and the committee voted unanimously to subpoena them. But the White House refused to turn them over, and the courts decided not to intervene in a confrontation between two branches of government.

Partisan politics continued in private. Mr. Baker and Mr. Thompson promoted a bogus explanation for the break-in, alleging that the C.I.A. had initially assisted and then undermined the Watergate burglars in order to damage the president.

Meanwhile, the Democratic staff unearthed the actual motive for the break-in: Mr. Nixon and his campaign manager, John Mitchell, were worried that Charles Rebozo, known as Bebe, would be identified as the man who had accepted $100,000 in cash for Mr. Nixon from the billionaire Howard Hughes. Mr. Mitchell had authorized breaking into the Watergate office of Larry O’Brien, chairman of the Democratic National Committee — who had been a paid consultant to Mr. Hughes — to see what Mr. O’Brien knew about the Rebozo transaction.

We also discovered a $100,000 payment from Mr. Hughes to Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic presidential candidate. Mr. Ervin shut down the hearings. “I was just preserving the two-party system,” he said jokingly to me afterward.

Yet for all its infighting, the committee played a crucial role in unearthing information that led to Mr. Nixon’s downfall. After our subpoena for the White House tapes was blocked in federal court, the special prosecutor issued his own. Mr. Nixon responded by having Mr. Cox fired, which led to the resignation of Attorney General Elliot L. Richardson and the deputy attorney general, William D. Ruckelshaus. Mr. Cox had opposed a deal under which a conservative Democratic senator, John Stennis, would review and verify summaries of the tapes. Under that deal, prosecutors, courts and the public would not have gained access to them.

The move backfired spectacularly. Public outrage over the Saturday Night Massacre, as it became known, encouraged lawyers in the special prosecutor’s office to aggressively pursue the tapes. Their arguments convinced the Supreme Court that in a criminal case, every citizen — even a president — must comply with a subpoena, and the tapes were released. Attention soon turned to a smoking-gun recording implicating Mr. Nixon in the cover-up. On Aug. 8, 1974, he resigned.

Two lessons emerge. First: Congressional committees are powerful tools for investigating the full range of abuse of power by a president and for passing reforms to avoid repetitions of those abuses. (Unfortunately, reforms enacted after Watergate were eroded over subsequent decades.) But committees have limited power to compel presidential compliance with demands for evidence.

Second, prosecutors can often obtain the critical evidence that committees can’t. But their job is to prosecute crimes. They are less likely to get to the bottom of executive abuses or to prevent their repetition. Most tellingly, special prosecutors, as part of the executive branch, can be dismissed by the president, while congressional committees are protected by the constitutional separation of powers.

That’s why the work of both is so important. Robert S. Mueller III has been appointed special counsel to look into possible Russian meddling in the 2016 campaign, an investigation that might cover both criminal and counterintelligence matters. Some senators say this will conflict with and perhaps necessarily limit congressional inquiries.

But that needn’t be the case. While prosecutors prefer not having congressional competition, a mature special prosecutor and a well-led congressional inquiry can coordinate over issues like witness immunity. Congress can creatively expand its witness list beyond prosecution targets and fill in critical details from “satellite” witnesses, as the Watergate committee did with Mr. Butterfield.

Bipartisanship will be crucial. Working with the evidence secured by prosecutors, congressional committees can provide a declassified narrative of Russian actions and whether Trump aides colluded. If the committee is aggressive, and its work is truly bipartisan, it can not only educate and reassure the public, but also legislate solutions to prevent future abuses.

A reclusive Mr. Nixon worked behind the scenes to impede investigators and prosecutors. He believed that his secret tapes would bring down John Dean; instead they fertilized the bipartisan outrage that brought about his own demise. But that bipartisanship didn’t exist when the Watergate committee began its work. In today’s hyperpartisan atmosphere, that is worth remembering.

Expositores: Oscar Vidarte (PUCP) Fernando González Vigil (Universidad del Pacífico) Inscripciones aquí. Leer más

Una retrospectiva para entender los próximos cuatro años. Leer más

En la conferencia se hará una presentación de los temas más relevantes del proceso de negociación se llevó a cabo desde el 2012, así como del acuerdo de paz firmado entre el Gobierno colombiano y la guerrilla de las FARC a finales del 2016. Se analizarán los desafíos y las... Leer más

El Observatorio de las Relaciones Peruano-Norteamericanas (ORPN) de la Universidad del Pacífico es un programa encargado de analizar y difundir información relevante sobre la situación política, económica y social de Estados Unidos y analizar, desde una perspectiva multidisciplinaria, su efecto en las relaciones bilaterales con el Perú.

© 2024 Universidad del Pacífico - Departamento Académico de Humanidades. Todos los derechos reservados.